The Buenos Aires-based Nueva Sociedad periodically asks me to explain some aspect of U.S. politics for their Spanish-language audience. Most recently, I was asked for a piece on the Fighting Oligarchy tour led by Bernie Sanders. The Spanish final is at the link. I’ll post the English text below.

After Donald Trump’s victory in the elections of November 2024, the Democratic Party faced an enormous leadership vacuum. Joe Biden had physically and mentally degenerated too much to be an effective public communicator. Kamala Harris disappeared following her painful loss. In his post-presidency, Barack Obama has continued to maintain relative silence. Who could speak for the party, wounded after another defeat at the hands of Donald Trump? Many in the party seemed to be behaving as if politics would carry on as normal, even though they had consistently communicated to the public that Trump represented a threat to democracy. Did they believe it?

As Trump entered office, he empowered Elon Musk, who had spent more than a quarter of a billion dollars on Trump’s campaign, to head up an invented agency. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE, to refer to the meme that appeals to Musk’s juvenile sense of humor) dismantled government agencies that are seen as part of the politically progressive “deep state”— foreign aid, consumer protection, and education. Although spending on salaries is a tiny fraction of the federal budget—between 4% and 5%–employees were fired in mass, arbitrary waves. Since there are federal employees all throughout the country, Republican elected officials holding town hall events for their constituents soon began to face angry crowds, concerned about loss of jobs, basic services and the lawless approach of DOGE. Republican leadership advised lawmakers to avoid having town halls altogether. In mid-April, three protesters were shot with a stun gun and removed from an event hosted by far-right congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, while voters elsewhere held meetings with empty chairs as a form of symbolic protest.

In this environment, the first opposition politician to step forward was Senator Bernie Sanders. Though Sanders is technically an independent and identifies as a democratic socialist, Sanders had been loyal to President Biden and did what he could for Kamala Harris. In the last days of Harris’s campaign, he endured crowds angry with him that he had not publicly confronted the administration, for example, for its support for the conduct of Israel’s war in Gaza. When Harris’s bid to appeal to disaffected Republicans and more centrist voters did not produce an electoral majority, Sanders immediately began speaking more forthrightly, and critically, of the Democratic party. This proved galvanizing at a time when Democratic leaders have had to confront that record numbers of Democrats are dissatisfied with their own party.

It has always been one of the strengths of Bernie Sanders, who is now 83, to speak to the kind of Trump voter that has faced economic decline and dislocation. He acknowledges that the economy is not working for all more easily than mainstream Democrats. But while the Republican party has built its brand of appealing to this sort of voter with a politics of class resentment in which class is defined mostly by educational attainment, Sanders insists that what still matters is economic exploitation. It is “the billionaires”—it has become difficult to think of the word without hearing it in Bernie’s non-rhotic accent as “billionaiahs”—who are responsible for the country’s inequalities and incomplete social safety net. The disproportionate power of the extremely wealthy over the political system could not have had a better demonstration than the richest man in the history of planet Earth, Elon Musk, devoted himself to eliminating middle-class jobs for teachers, park rangers, and civil servants.

Another of Sanders’ strengths is the ability to draw large crowds. And so, in late February, at a time when virtually no other Democrat had a public strategy for confroting Trump, Sanders went back on the road. He began his “Fighting Oligarchy” tour not in heavily progressive areas, but in electoral districts held by the Republicans who now seemed afraid to talk to their own voters. The goal was to pressure Republicans to stand up to Trump and DOGE. For example, Sanders visited Kenosha, Wisconsin on March 7. The city of about 100,000 was once a car manufacturing hub with unionized labor, but is now home to an Amazon warehouse and has moved heavily towards Trump.

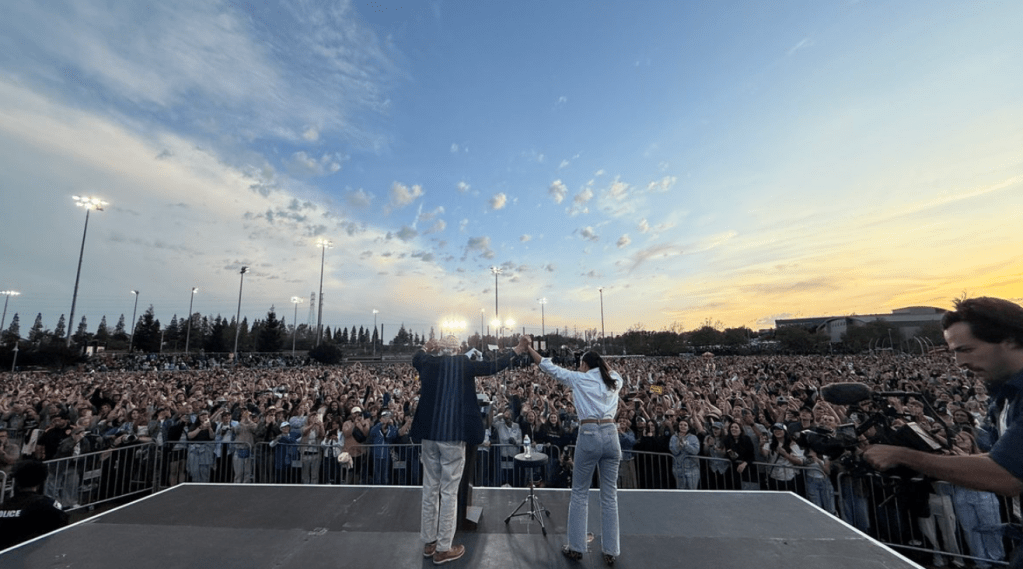

But the meaning of the tour changed quickly as it became evident that Sanders was capturing something much larger. The crowds he was attracting exceeded expectations. Instead of theaters, he moved to arenas. Then he moved outdoors. He added some traditionally Democratic cities to the list, and was met by 34,000 people in Denver, Colorado, and 36,000 in Los Angeles—the latter the largest crowd of his career, including his two presidential campaigns. But there were huge crowds in less-expected places too: 20,000 in Salt Lake City, Utah, 26,000 in Folsom, California in the working-class Central Valley, 9,100 in Missoula, Montana, and 12,500 people in a county in Idaho that voted 72% for Trump. New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez began joining him at every rally, echoing his call for a political renewal. “An extreme concentration of power, greed, and corruption is taking over the country like never before,” Ocasio-Cortez says.

Bernie’s fundamental message hasn’t changed much. “We have an economy today that is working very well for the billionaire class,” he told concertgoers at the music festival at Coachella, “but not for working families.” He calls for guaranteed healthcare as a human right, which will require confronting insurance companies. He calls for action on climate change, which will require confronting fossil fuel companies. And he now calls for ending the war in Gaza, which—and this he does not say out loud—will require confronting the Democratic party too. Everywhere he goes, Sanders’ organizing team collects names and contact information of those who attend, connecting them to other anti-Trump events and encouraging them to remain politically active. It has taken a critic of the Democratic party to mobilize the Party’s voters.

One of the achievements of the tour has been to demonstrate—as Sanders’ primary campaigns once revealed the existence of a social-democratic voter—that the anti-Trump coalition remains, and remains eager to confront Trump in spite of his victory in November. “We are living in a moment of extraordinary danger,” Sanders told the crowd in Los Angeles, “How we respond to this moment will not only impact our lives, but will impact the lives of our kids and future generations.” And though no one has matched his ability to draw out the multitudes, other Democrats have since taken more publicly oppositional stances. Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey spoke for 25 consecutive hours from the floor of the Senate; Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland visited El Salvador’s CECOT prison to speak to Maryland resident Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who the Trump administration deported because of administrative error and who has become emblematic of its new deportation regime. The enthusiastic response to Bernie’s tour helped lift some of the fear of Trump, even for those who do not fully share his politics.

Part of the purpose of the tour is also to pass the progressive baton to Ocasio-Cortez. Sanders is too old to be a candidate for the presidency again. Ocasio-Cortez (at 35) is technically eligible but probably too young. (More realistic next steps for Ocasio-Cortez would be increased responsibilities in the House, such as Chair of the Oversight Committee, or to challenge for the Senate seat of Chuck Schumer, who angered rank-and-file Democrats with his decision to pass a budget bill while DOGE was operating outside the law.) Polls show that Ocasio-Cortez is no longer on the socialist fringe of the party, but someone that Democrats broadly in high esteem. In an April poll, 19% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents said she “best reflects the core values” of the party—more than any single candidate, including Kamala Harris (chosen by 17%) or Barack Obama (identified by 7%). Some Republicans, who used to like to put Ocasio Cortez forward as the face of the Democratic party in an attempt to make it seem extremist, are now beginning to worry that she will have the talent to respond to the building backlash against Trump, who has, after only 100 days, already lost significant support.

Ocasio-Cortez’s ascent also reveals divisions within the party about how to best confront Trump. Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez believe that both parties are too beholden to corporate interests. They have a certain appeal to people who feel that they don’t represent “the system” – after Trump’s election, AOC heard from many people who had voted for her and for Trump, praising both for their “authenticity.” “Plenty of politicians on both sides of the aisle feel threatened by rising class consciousness,” AOC posted to her social media accounts in late April.

Virtually all Democrats agree that the party needs to do a better job of crafting a compelling economic message. But not everyone agrees that “class consciousness” is the right way to describe what is going on. Senator Elisa Slotkin of Michigan has criticized the “oligarchy” framing of Sanders, saying that it sounds like a word coming from the faculty lounge and not one that will resonate with ordinary Americans. She wants the party to stop being, as she describes it, “weak and woke.” There will be a complicated contest between those who think that the public will be yearning for a return to something normal after Trump and those who think that his re-election reveals that the system needs a major overhaul. Debates in the party remain about whether the party is “too centrist” or “too leftist.” (The answer is assuredly both, given that it is a national party trying to reach many audiences, some of whom think that it is too centrist and some of which think that it is too leftist.)

In their classic 1986 work of political science, Paper Stones: A History of Electoral Socialism, Adam Przeworski and John Sprague stated plainly: “No political party ever won an electoral majority on a program offering a socialist transformation of society.” Every leftist party that won a majority had to find ways to appeal to the middle class. In truth, the Sanders and Ocasio Cortez agenda is a social democratic one and not particularly radical by global standards. Nevertheless, no one knows what elections will look like with Trump in office, and whether he will accept the results if he loses. No one knows what might happen between now and the next major elections, or how best to hold the anti-Trump coalition together. But for now, 72% of Democrats are telling pollsters that they prefer Democrats like Sanders and Ocasio Cortez who will “fight harder” for the party’s priorities, rather than the ones who are trying to find common ground with Trump. People will continue to debate the content of what is said at the “Fighting Oligarchy” rallies. But the form is already a winner.

Leave a comment