I don’t want to overdraw a very imprecise analogy, but I’ve been thinking about certain connections between the U.S. right and authoritarian projects in Latin America’s past. All of a sudden, there was a news hook to talk about it:

Anthony D’Esposito, a congressman from New York, posted a picture on X last week of an undocumented immigrant flashing two middle fingers after being arraigned for allegedly assaulting two NYPD officers. “We feel the same way about you,” D’Esposito wrote. “Holla at the cartels and have them escort you back.” But Republican Congressman Mike Collins took it a step further: “Or we could buy him a ticket on Pinochet Air for a free helicopter ride back.” His post was flagged as violent speech, but it was allowed to stand on the grounds that “it may be in the public’s interest for the Post to remain accessible.”

Collins probably considers his statement a joke intended to communicate his views of migrants, and it is best not to overreact to behavior that is designed to provoke. But his post also reflects the mainstreaming of authoritarianism in the GOP. Since at least 2016, members of the Proud Boys—the extremist group that Trump told to “stand back and stand by” in the event he lost the 2020 election—have worn shirts with slogans like “Pinochet did nothing wrong” or “Pinochet’s Helicopter Rides.” Now a Republican in Congress is repeating them.

But the comparisons do not end there, as I get to in this short piece in The New Republic.

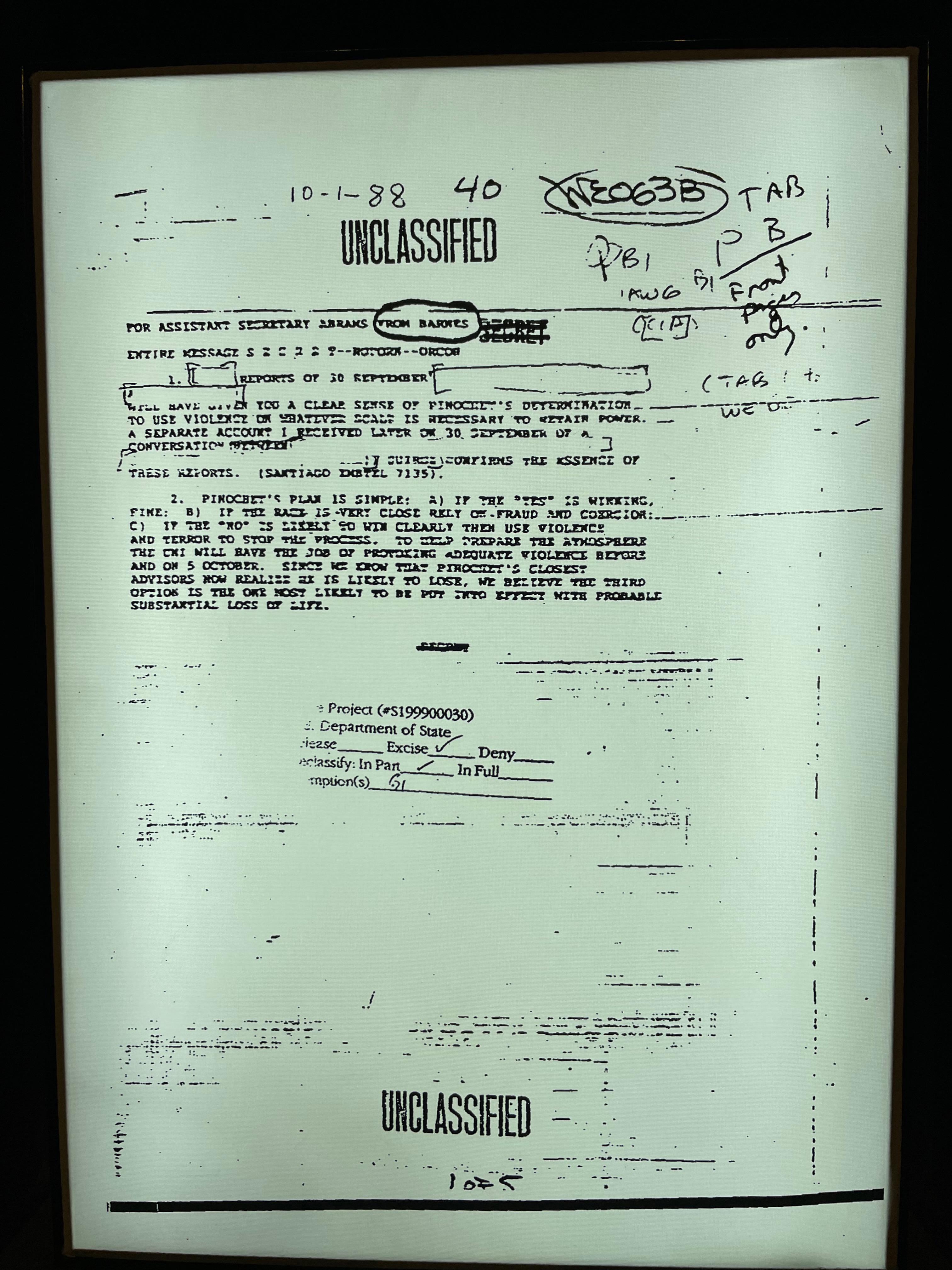

General Pinochet took power in a coup d’état on September 11, 1973, deposing elected Marxist President Salvador Allende amid an economic crisis and extreme civic polarization. Fifteen years later Pinochet was under domestic and international pressure to allow a plebiscite to determine whether to keep him in power. Pinochet argued that a “no” vote, which would restore a competitive electoral democracy, would bring back the chaos of the Allende years. The “no” coalition, which was allowed to organize on the ground and advertise on television, brought together a broad group of parties. Even the United States, whose policies had helped Pinochet come to power, pushed for the results to be respected. Harry Barnes, Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to Chile, warned that “Pinochet’s plan is simple: (a) If the “yes” is winning, fine: (b) If the race is very close rely on fraud and coercion: (c) If the “no” is likely to win clearly then use violence and terror to stop the process.”

There are several points that I wanted to make that didn’t make the final cut of the piece.

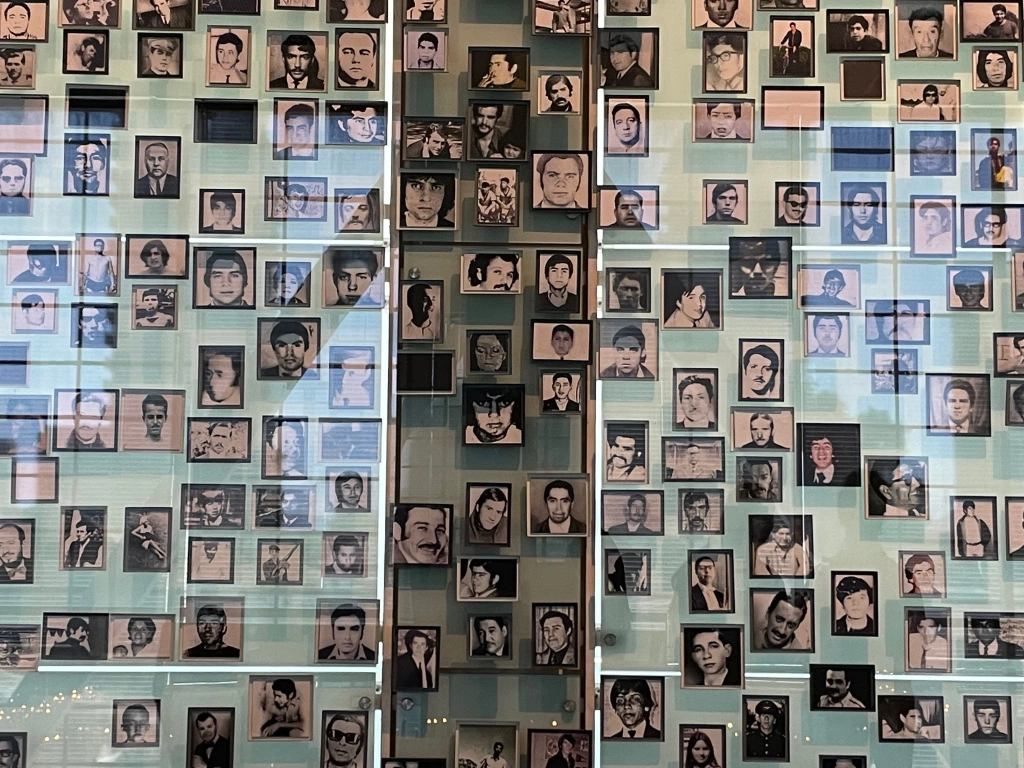

The appeal of Pinochet for an international audience today is twofold. The story that Pinochet told of his actions were not those of the man who ended democracy in a country proud of its democratic traditions, but of the man who saved Chile from leftist ruin. The thousands who were killed, and the tens of thousands who were tortured, were enemies of the nation, not worthy of legal rights or human dignity. Like many right-wing intellectuals in the U.S. today, Pinochet’s advisors believed that the left had ruined Chilean institutions and had to be extirpated from them. His government sent a military official, active or retired, to replace the rector in every university in the country in the first days after the coup of 1973, claiming that they had become centers for the “preaching of hatred.” Programs perceived as left-wing were closed; students were arrested, professors fired, and books burned. Instructors were told to promote “national values,” and students encouraged to enroll in programs in business and engineering.

The other work that Pinochet does for the contemporary right is to make possible a combination of authoritarianism and libertarianism. Pinochet’s government remade its economy with a blueprint provided by economists trained at the University of Chicago. In many right-wing circles, it was and remains celebrated for the creation and maintenance of a “free market” insulated from social pressures. Its economic reforms, some hold, advanced the cause of freedom, whereas the democratically elected socialist was held responsible for destroying freedom. Influential right-wing economist Friedrich Hayek, for example, visited Chile twice and announced that he preferred a capitalist dictator to a democratic government without capitalism. Even as many Trump-aligned intellectuals move towards more statist economic ideas, Pinochet-style “authoritarian libertarianism” remains a significant ingredient on the U.S. right, promising utopia if freedom’s enemies can only be pushed aside.

Leave a comment