For The New Republic, I have a review of the Sebastian Edwards book “The Chile Project.”

It began underground. In October 2019, high school students led protests in the city of Santiago, spurred by an increase in public transit fares. They began to jump the turnstiles, and soon more and more people joined them. Chile’s carabineros used tear gas to expel people from the subway stations. Soon, the city—and the country—were in revolt. Millions protested peacefully, and sometimes the atmosphere was joyful. Musicians played and crowds sang the anthem of the Popular Unity government that had been removed in a coup d’état in 1973: “El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido: The people, united, will never be defeated.” But there was also tension: Barricades went up, stores were looted, metro stations burned, and young people dismantled streets with chisels to throw cobblestones at police.

Above ground, in their modern high-rises, the greatest beneficiaries of Chile’s economic growth were shocked. The country, by many metrics, seemed to be doing well. It is one of only four in Latin America to have joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the club of “developed” countries. Its GDP per capita has risen from the middle range of Latin American countries to among the very highest. Its poverty rate, over 60 percent in 1987, had declined to 8 percent, and inequality (though still very high) had fallen, too. But the country’s history has given its market economy a sinister undercurrent.

In 1970, the Socialist Salvador Allende was elected president, promising a democratic and legal path to socialism—Chilean-style, a socialism “with red wine and empanadas.” Three years later, he was ousted by a military coup. The dictatorship led by Augusto Pinochet murdered and exiled many of its opponents—and worked to remake the relationship between state, economy, and society. To do the latter, it followed the advice of a group of economists known as the “Chicago Boys,” for most of them had trained at the University of Chicago, where their teachers included Milton Friedman (who became the most famous) and his colleague Al Harberger (who cared most about Chilean development). But Chicago’s economics department was not just any program. Its tendency was to trust markets and to mistrust regulation. The Chicago Boys extended the reach of market logic as deeply as they could: slashing state employment, dismantling unions, and creating a privatized pension system. By the time the regime left power in 1990, Chile was considered among the most “neoliberal” societies on Earth.

Parts of the Pinochet-era economic policy persist in Chile today, where the left sees them as a poisoned legacy of the dictatorship. Many books on the left—think of Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine, for example—have linked Pinochet’s state terrorism to his Friedmanite libertarian economic program. When Friedman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1976, during the ceremony a protester heckled, “Freedom for Chile!… Crush capitalism!” On the right, meanwhile, figures such as Joaquín Lavín have celebrated Chile’s market reforms, praising the nation’s “Silent Revolution” for saving the country. When George W. Bush proposed a partial privatization of Social Security in 2005, he was following the Chilean template.

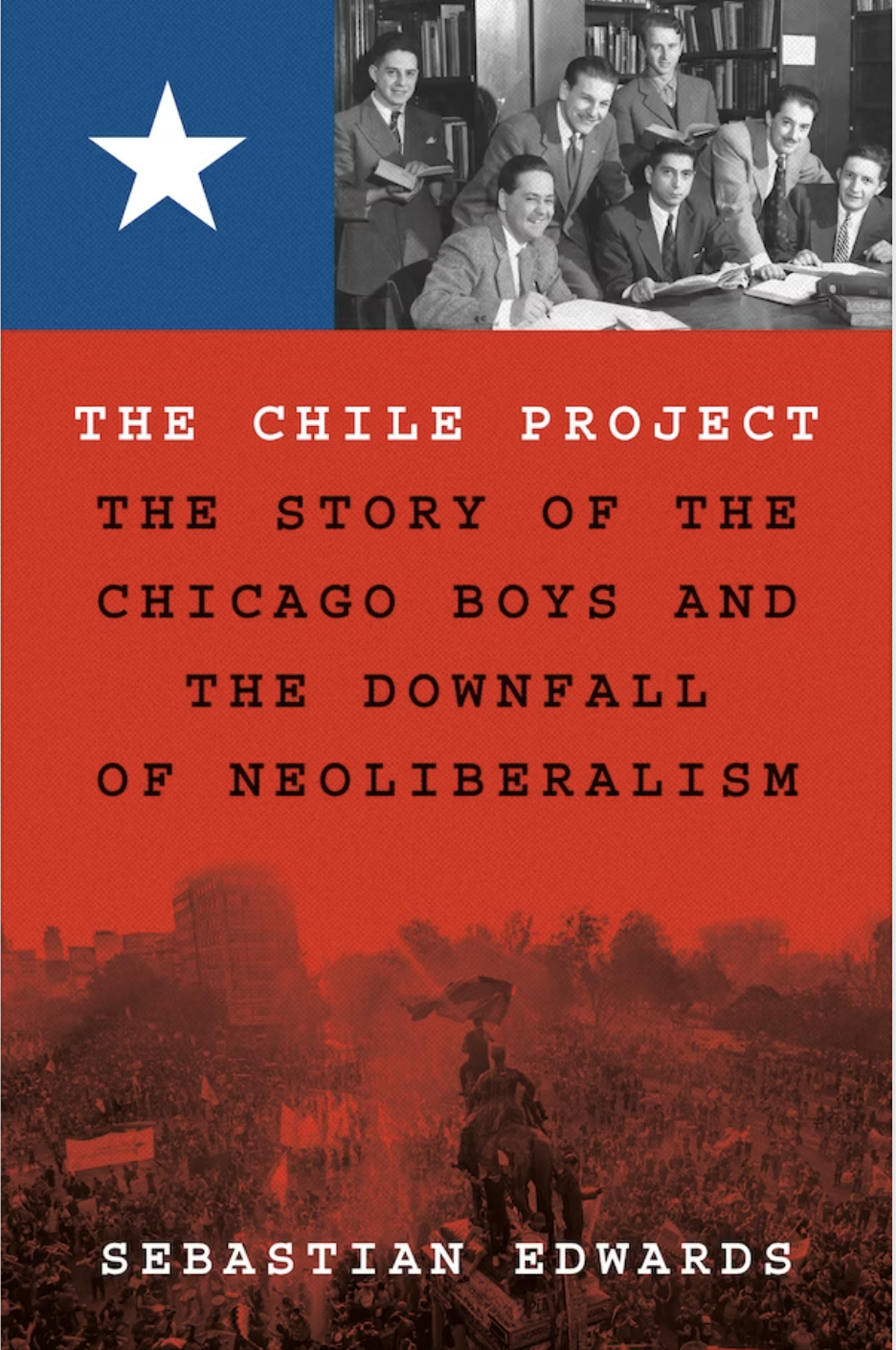

In his account of this economic history, The Chile Project, Sebastian Edwards tries to steer a middle path. He acknowledges errors driven by ideological Friedman-like inflexibility. But he wants to rescue the reputation of the more pragmatic Chicago Boys, like his former teacher Harberger. He attempts to reckon with important mistakes, while still reclaiming Chile’s market economy from the legacy of the dictatorship. His approach, grounded in archival research and economic analysis, is a careful and serious one. Yet the project is far from simple: how to separate the vision of liberation that Pinochet’s authoritarian regime presented from the Chicago ideas of markets as freedom?

Read the whole review here.

Leave a comment